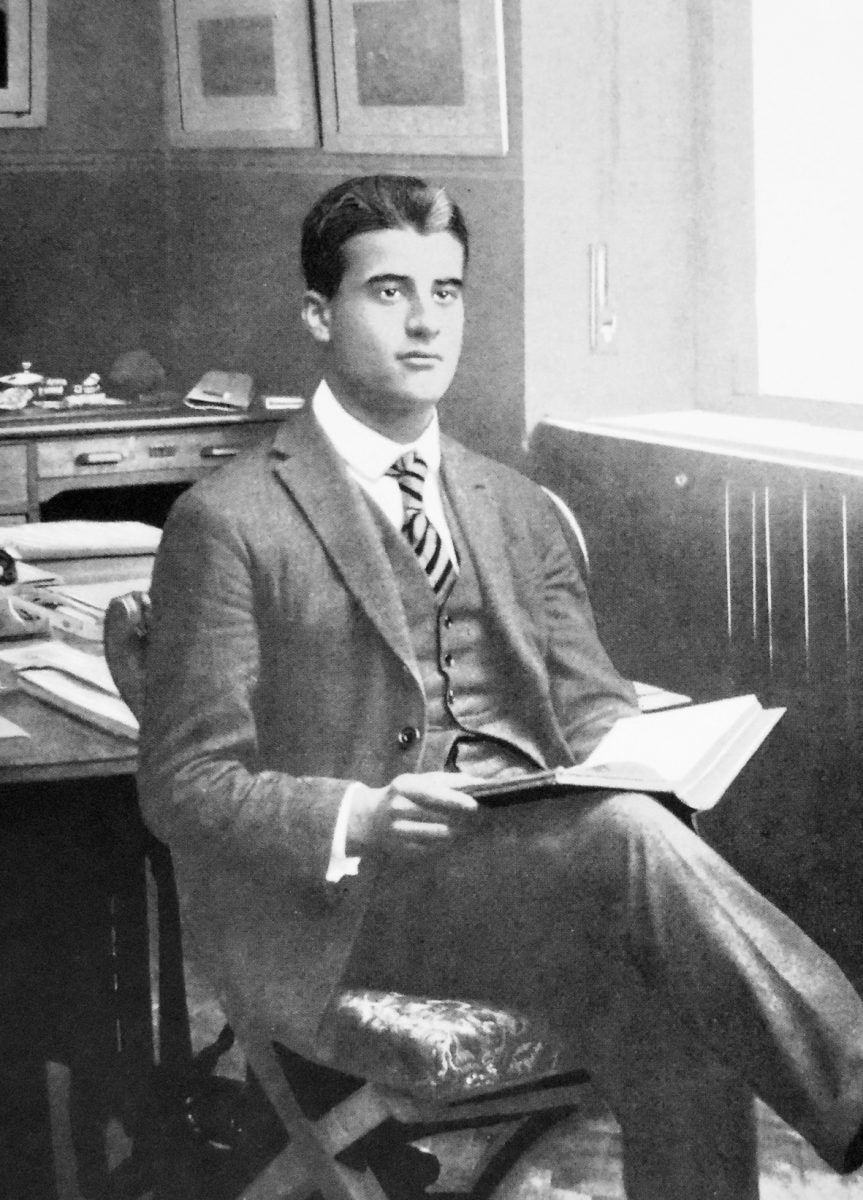

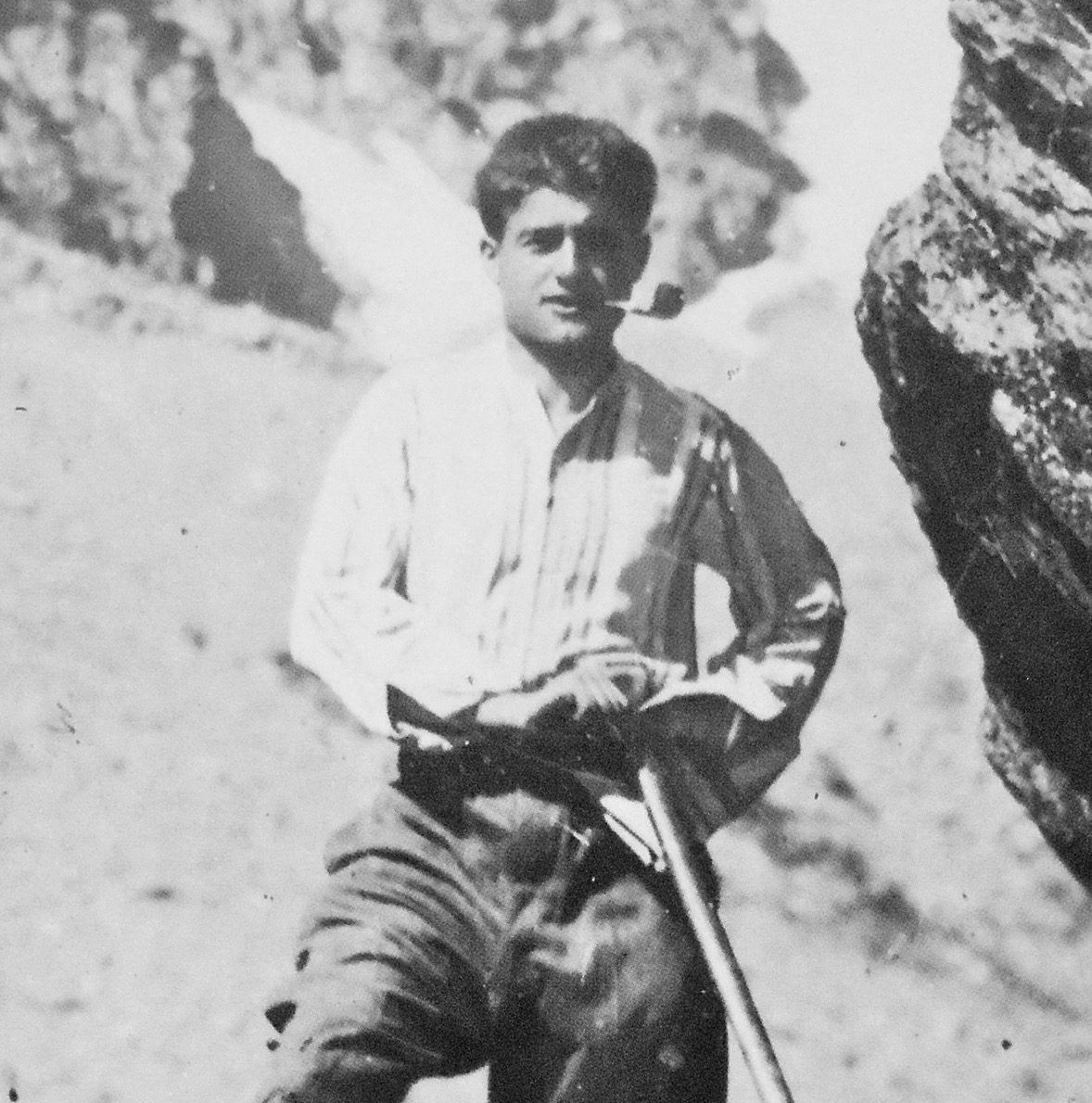

“Verso l’alto” or “toward the top” is the phrase Pier Giorgio Frassati, a mountaineer and servant of the church, inscribed on a photo picturing his arduous climb up Val di Lanzo mountain in Italy. In the photo, Frassati is nearing the pinnacle of the rugged cliff on which he hangs, peering toward the rocky peak preparing to make his next move. Frassati’s “Verso l’alto” mindset led him not only to reach the top of Val di Lanzo, but also guided him through a life that would lead to sainthood.

Frassati stands as an example of what the school, through a Christ-centered education, aims to shape: an empathetic and kind person, seeking to provide service for others in an overall Christ-like way, or in other words “a person for others.” He had the desire to truly know God in his life which he carried out through service. This is what his motto, “toward the top,” aims to communicate: a continual upward “climb” toward Christ throughout life.

Frassati’s story and example within the school first came to my attention during a summer discipleship class led by theology teachers Angela Basse and Lydia Sorrels and stuck in my mind as the school began its new term. More recently, I wrote a news story on his canonization, which once again brought to mind his role within the school and what he meant in saying “toward the top.” As I wrote the story, I began to question if the school’s application of “towards the top” aligns with Frassati’s original focus. I truly believe that the school aims to provide a “Christ-centered education,” but situated in the modern age, is it successful in this effort or does it fall into a more secular approach in our increasingly secular society?

In his book “Practicing Christians, Practical Atheists,” Professor Phil Davignon outlines the “Christ-centered education.”

“A truly Christian education must ensure its curriculum, course content, and teaching methods facilitate a deeper experience of reality and foster growth in wisdom and virtue, rather than merely delivering useful information,” Davignon wrote.

Ideally, a Christian education adopts a multi-dimensional approach to education seeking to evoke a sense of awe or wonder of knowledge that inspires a love and appreciation for learning instead of requiring the memorization of material for the sake of meeting an end—such as a test, final, or just passing a class.

According to theologian Alexander Schmemann, God is not separated from the material world, but instead the material world is the revelation of God. When applied to education, we must treat the viewing of the material world, man’s role in it, and each lesson it teaches as a greater revelation of the Creator. Or in Davignon’s words, this should look like teaching in a way that points to a “deeper meaning of creation and invites us to worship.”

To truly provide a Christian education, students should practice a love of learning for the sake of learning and growing closer to God rather than taking in information to achieve something or meet an end. In other words, students should embody Frassati’s “toward the top” as a call to treat learning as a way to come closer to Christ rather than a method to reach worldly success.

In contrast to this Christian way of teaching, society has shifted toward a more functional form of education. Today, schools prepare students to enter a workforce driven by monetary gain by educating them on more practical knowledge that only acts to serve them a certain way. This, in turn, creates the idea that the “top” is worldly success and that going toward the top means taking steps to achieve this worldly success.

Many educational institutions have ceased sharing knowledge for the sake of learning, and now share knowledge simply so that students may get some material gain out of it. The issue with this form of thinking is that it frames education in a way that only gives value to learning if someone can get something in return, and so if education has no potential for material gain, then it becomes inherently useless. This thought process effectively separates God from His creation, in that God as the Creator gives creation its value. Schmemann explains this issue.

Though many Christian schools claim to be providing a “Christ-centered education,” in reality, they fall short in their practices of maintaining Christ as their main focus by only adding bits of theology on top of a secular education. They teach as though God does not fit into creation, then slap on some “spiritual aspect” when in reality He is what gives creation meaning.

To properly provide a Christ-centered education, and therefore invite worship into daily life, we must simply acknowledge Christ’s work in creation and view the “top” not as worldly success, but our goal in reaching Christ.

So, does Bishop McGuinness truly provide a Christ-centered education, or does it simply fall to a more secular approach? Does the school’s definition of “toward the top” still coincide with Frassati’s original statement?

One of the school’s main attempts to incorporate Christ into education is through “spiritual opportunities,” which were required up until last year. After the mandate to attend spiritual opportunities was lifted, attendance dwindled, which leads me to question whether students find them meaningful if they actively choose not to partake.

Many times when I enter the chapel, I find that students consistently remain disengaged talking to friends or playing on their phones. Other times, I enter the chapel to find it more than half empty while the same three people sit quietly in the back. The main issue with this form of spiritual opportunity is its failure to create virtuous habits within those who participate. If we truly want students to find meaning in spiritual opportunities so that they may grow in their relationships with God, we must integrate some sort of habit forming routine that places connection with Christ over fulfillment of requirement.

In addition, take into consideration the school’s monthly Masses. Within the Mass, a time that’s meant for reverence and worship that is celebrated in the school auditorium, the majority of students choose not to fully participate and instead decide to deviate to side conversations with friends or once again take dog filter snap chat photos on their phones. One issue with Mass is the informality of its setting. We celebrate all-school Mass in the same place we hold pep rallies, holiday assemblies and school plays, which I believe is a large contributor to students’ indifference toward the celebration. Another contribution to this issue is students’ fear of judgment from their peers. Even as a Catholic school, students still might be considered strange for being “overly religious.”

Another issue lies with the school’s use of service requirements. Often, the requirement can lead to a type of transactional service where many students only complete hours in order to meet the graduation requirement or fulfill their obligation for a theology grade. While his requirement has the right intention, to give students the opportunity to give back, the 90 hour requirement sometimes creates an impersonal type of service that defeats the original purpose of completing service in the first place: to empty oneself for the other without expecting anything in return. To better expose students to the purpose of service, we should implement a service policy that emphasizes experience over requirement, so students can better realize the purpose of actual Christian service.

Finally, consider how teachers are incorporating Christ into their daily lessons. In most classes, if anything they might start class with prayer, but most stop at that and never give any mention to Christ’s teaching let alone integrate it into any lesson. With such a focus on academic success, many teachers either don’t have the time to or don’t know how to fully permeate the teachings of Christ within their daily lesson.

Moving forward

In laying out these points, it is necessary to say that I do believe that Bishop McGuinness is successful in providing one of if not the best high school education in the state. In addition, after hearing from past graduates, I believe the school more than adequately prepares its students for college, and provides an environment that fosters high achievement in almost every area of activity because of its focus on success. However, I also maintain that many of the school’s issues in Catholic education stem from this focus. With such an aim of being the best and working “toward the top,” the school can sometimes forget that the top we’re working toward is not only success in AP scores, state titles and college admissions, but a growth toward and understanding of Christ within our lives.

With these problems in mind, if the school truly desires to move beyond secular education and work to climb “toward the top,” it must move past the world’s expectations of success, and better strive to see God in all aspects of education. A Christ-centered education should start students on a path leading to a love of learning through wonder and awe. To truly align with Saint Pier Giorgio’s climb, the school must be reminded that the “top” is not simply worldly success—but an ever-continuing search for Christ’s truth and light in the face of distraction of darkness.